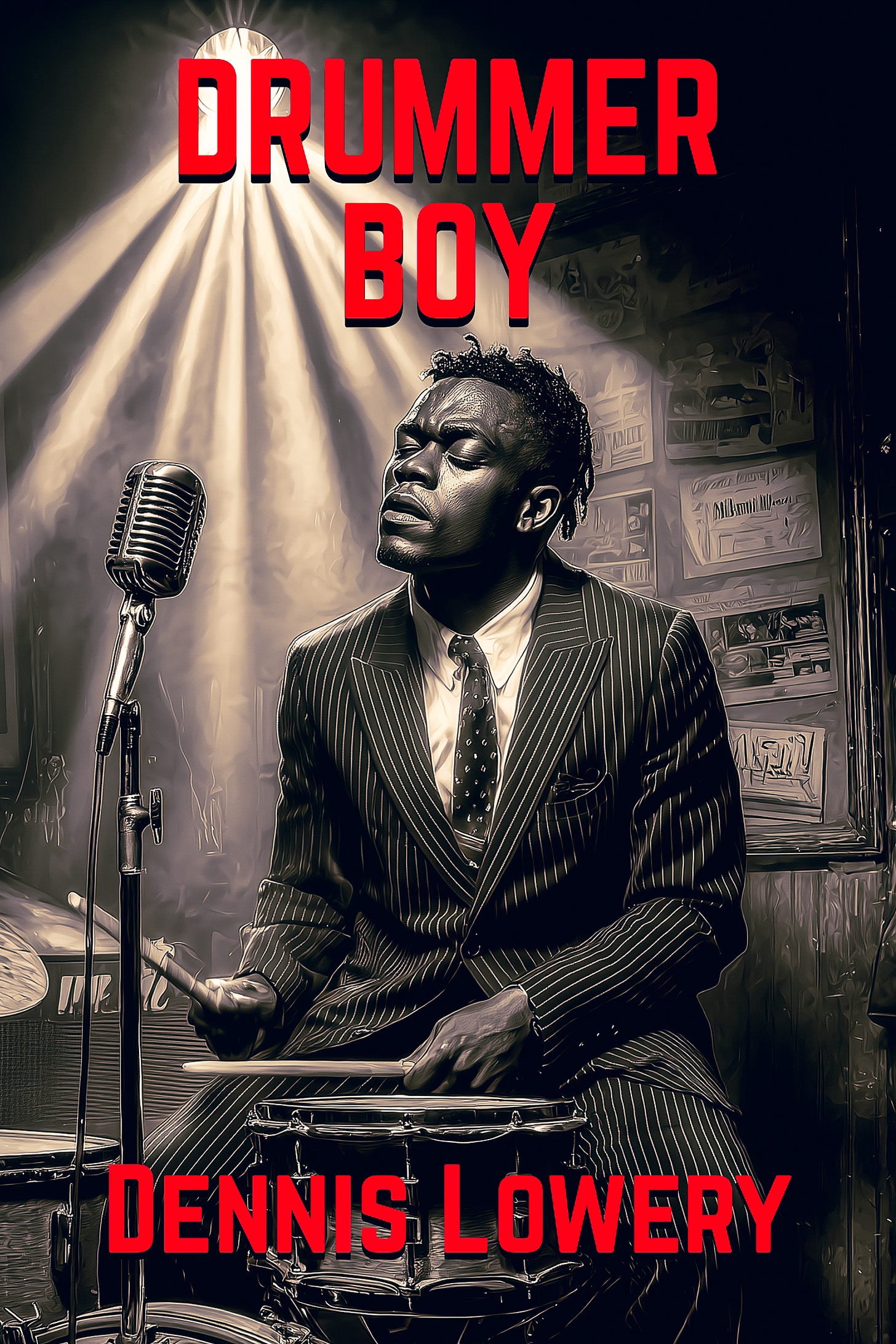

DRUMMER BOY

December 24, 1942

Author’s Note:

Drummer Boy is a standalone short story set in the world of THE RED NIGHT (a story in development for 2026). You don’t need to know anything about that larger story to read this one. It’s complete on its own. But for readers who later enter that world, this night—and this man—will matter.

Hammond ‘Ivory’ Jones is a working jazz drummer in December 1942. He’s been drafted. He knows he’ll be leaving soon. What he doesn’t know is whether he’ll ever come back to the life he’s built—his music, the rooms he plays, the people who recognize him by sound before they recognize his face.

This story takes place on his last uninterrupted night before that door—that life—closes.

Ivory isn’t trying to make a statement, and he isn’t being brave. He plays his final song, honestly, because it’s the one thing still wholly his. It’s how he marks the moment before he has to leave, and how he holds onto the quiet hope—never spoken aloud—that the life he’s stepping away from might still be there when he returns.

In THE RED NIGHT, Ivory exists mostly in absence and aftermath. He is important but not a central figure in that story. And his disappearance matters. This piece gives him a moment of his own before that happens.

Read on its own, Drummer Boy is a story about a man, a room, and a night when music must do more work than usual.

Read later alongside THE RED NIGHT, it becomes something else: a glimpse of what the world looked like just before it lost him.

— Dennis Lowery

Listen to the song from the story.

THE STORY

December 24, 1942

Sun well-set behind him, Ivory got there before the door sign flipped to OPEN. The ramshackle club still smelled like yesterday. Stale smoke trapped in wood, beer sunk into the grain of the bar, and a thin metallic tang from the harbor that never really left. The cold followed him inside, clinging to his coat and the cuffs of his trousers.

A Christmas garland sagged above the bar like it had been hung out of obligation. Someone—maybe the bartender’s wife, maybe the bartender himself in a rare soft mood—had braided it from rationed paper and strands of tinsel that looked scavenged from better years. In the far corner near the window, a small evergreen stood in a bucket, its needles already shedding. It wore three ornaments, none of them matching. One was a dull, silver metal ball with a dent. One was a hand-cut cardboard star. The third was a red ribbon tied in a knot that could’ve been pretty if it hadn’t been frayed.

Behind the bar, Gus wiped the same spot with the same rag, slow and methodical. His hair had gone grayer since last Christmas. Everybody showed signs of the years’ strain.

“You’re early,” Gus said without looking up.

Ivory shrugged out of his coat and draped it over the back of a chair near the stage. Not the best chair. Not the closest. One of the ones along the wall, where you could see the room without quite being in it.

“Couldn’t sit at home,” Ivory said.

That was true. Also, not the whole of it.

Gus finally looked at him. His eyes went, as they always did, to Ivory’s hands, knowing he’d get in fights—in the ring and out—checking they were still intact, still steady. Ivory had a drummer’s hands. Long fingers. Callused pads. Knuckles that had taken countless rimshots. Hands that had been the young man’s gift since he’d first seen him as a kid on a street corner, striking a beat on an old bucket.

“You eat?” Gus asked.

Ivory shook his head.

Gus reached under the bar and came up with a small plate. Two pieces of toasted bread gone cold. A smear of something that might’ve been butter if butter still existed in honest quantities. Ham so thin it barely counted as a slice.

“Okay,” Gus said. “Eat.”

Ivory ate. A man who knew better than to argue with small blessings.

From behind Gus—in the office, the broom closet, whatever name a man gave a space he could disappear into—the radio crackled. Gus kept it low on purpose, like volume alone could keep the war from marching through the walls.

A clipped voice came through in fragments:

“…convoy losses…”

“…ration board…”

“…North Africa…”

“…Guadalcanal…”

“…telegram…”

Static. Then another voice, too bright, trying to sound useful, hopeful.

“…victory gardens…”

“…bond drive…”

“…keep faith…”

Gus reached in and turned the knob down with the same care he used to pour whiskey in the old days, before everything came with rules.

Ivory finished the bread. It didn’t fill him. It couldn’t.

“The boys coming?” Gus asked.

“Yeah,” Ivory said. “They always do.”

Gus nodded and went back to wiping the bar. The rag moved in orbits, steady as a brushed snare. Ivory watched it until Gus’s circles started to feel like timekeeping.

Ivory took his sticks from his coat pocket and rolled them between his fingers. He didn’t tap them yet. He didn’t want to stir the room.

Outside, a ship’s horn sounded—long and low through the window as vibration more than sound. The harbor was busy even on Christmas Eve. Especially with the war on, more things moved, materiel and men.

Ivory listened until the sound faded. Then to the quiet behind it.

He told himself—again—that tonight was just a set. Just music. Just work.

But it wasn’t. It was more to him.

The door opened with a rush of cold air. Calvin, the bass player, stamped slush off his boots, the smell of damp wool trailing behind him, and lifted two fingers at Gus. He looked older than he was. They all did, once the war started chewing on young men.

“You beat me,” Calvin said to Ivory, hauling his bass case toward the corner. “That’s new.”

Ivory didn’t flash his usual bright smile and gave him a look that said: Don’t make me talk.

Calvin read it. He always did. He set the case down and rubbed his hands together hard, bringing blood back into them.

“You hear about Benny?” Calvin asked, keeping his voice low.

Ivory’s stomach tightened. “Which Benny?”

Calvin shook his head once. “From Forty-Seventh. Played guitar. You sat in with him that time.”

Ivory remembered. He played a ’36 Gibson Sunset with a red spruce top. Thin kid. Sure-fingered, smooth playing. Serious musician.

“Training accident,” Calvin said. “Didn’t even get shipped.”

Ivory stared at his sticks. He imagined Benny’s hands—what he could draw from his Gibson—and didn’t finish the thought.

Calvin cleared his throat. “Sorry. War talk.”

“It’s fine,” Ivory said. It wasn’t.

Leon came in next, coat collar turned up, horn case knocking against his knee. His eyes were bloodshot—cold or lack of sleep, Ivory couldn’t tell.

“You boys hear that?” Leon said, nodding toward the radio. “They say we’re turning a corner. Again.”

Gus made a sound that might’ve been a laugh.

Leon shrugged and opened his case. He assembled the sax with the care of a man putting something dangerous back together. He tested two notes under his breath. They sounded like questions.

Miss Lottie arrived last, as she always did. Not late. On her own clock. Her coat was too light for the weather, her gloves worn through at the fingertips. She didn’t smile much. Even less now. She took in the rationed garland and the tired evergreen and made a face.

“Merry Christmas,” she said flatly.

“Merry Christmas, Miss Lottie,” Gus said.

Lottie looked at Ivory for a long second, then nodded once. Not warmth. Respect.

That mattered. She knew.

The club filled slowly. Dockmen in pea coats. Two sailors on shore leave, their laughter too loud, eyes too young. Women in hats and coats that had seen better years. An old man with a factory badge pinned to his lapel like proof he was still useful. A kid who looked sixteen trying to pass for older.

People came because they needed a place to drink and forget. Or to remember. They didn’t mind that all Gus served now was thin beer and cut-rate blended whiskey—spirits stretched with grain alcohol—that cost more than the good stuff had pre-war.

The room carried a strange quiet under its noise. Joy was allowed, but only in small doses.

Ivory watched from his chair. He studied the door. The bar mirror. The evergreen shed needles into the bucket like it was tired of pretending.

Then she came in.

No announcement. No pause for effect. Just a woman stepping out of the cold and into smoke like she’d done before.

She wore a dark cloth coat with the collar turned up. Her hair was pinned under a handmade hat. She stood near the door long enough for her eyes to adjust.

Then she saw Ivory.

He felt it immediately. Not like a jolt. Like weight.

He didn’t wave. He didn’t smile. He didn’t stand.

He simply looked back and held it.

That was how it had always been between them—close enough to feel, never close enough to claim. He’d told himself it was restraint. Respect. The truth was simpler. He hadn’t asked her, and she hadn’t pressed him.

She moved to a table near the edge of the stage where the light thinned. Not hiding. Not asking. Just present.

Ivory turned his sticks in his hands until the urge to speak passed.

The night could start now.

Gus came around the bar with two glasses. He set one near Ivory without asking.

“What’s that?” Ivory said.

“Don’t matter,” Gus answered. “Drink it.” He paused, “You gonna tell them?” He gestured at the people who’d found tables, watching the stages as they drank. “You gonna tell her?”

Ivory’s mouth tightened, Lottie’d told him. “No. Not their business.” He didn’t say the woman already suspected.

Gus held his eyes a moment longer than usual. “Guess they’ll know when you’re gone then.” He moved away, shaking his head.

Miss Lottie slid onto the piano bench and cracked her fingers, sharp and quick, like knuckles before a fight. Leon adjusted his reed. Calvin lifted the bass and settled it against his shoulder, the wood creaking softly as it took his weight.

Ivory moved to the kit. It was small—snare, bass, hi-hat, one ride cymbal dulled by years of smoke, a tom that complained if you hit it wrong. Enough. More than enough.

The stage sat at eye level, marked separately from the room only by light. Tables close enough that Ivory could see faces clearly. Close enough that they could see him breathe.

He checked the pedals, tightened the snare, tapped the rim once—private, not a count. Then he nodded to Calvin.

The bass came in low and steady. Lottie laid down a chord that held without showing off. Leon breathed a note into the room, cautious, like testing ice.

Ivory brought the brushes up and counted them in.

They started with standards. Nothing seasonal. Blues that kept the roof up. Swing that didn’t pretend too hard. Music that let people move without demanding they feel too much too fast.

A pair of sailors tried dancing with two women. One stepped on his partner’s foot. They laughed and tried again. A woman let herself be spun once and then retreated to her chair, smiling despite herself.

Ivory held the tempo as if holding something fragile. He didn’t rush it. Didn’t dress it up. He let the rhythm do its job.

Between numbers, people clapped. Someone whistled. A voice near the bar called out, “Merry Christmas,” awkward but sincere.

Ivory didn’t speak. He never did. He let the drums talk for him. Tonight, that felt safer.

At the break, Calvin leaned toward him, barely moving his mouth.

“You really going?” he asked.

Ivory didn’t pretend to not understand. He darted a look at Lottie, who ignored the glance.

The woman sat with her hands folded in her lap. She wasn’t looking at the stage now. She was looking down, as if giving him room to decide.

Ivory turned back to Calvin. “Yeah,” he said.

Clueless to the exchange with Calvin, Leon rolled his shoulders. “Don’t tell me we playin’ ‘Jingle Bells.’”

Lottie snorted. “I’m not playing ‘Jingle Bells,’ no, sir…”

A thin laugh moved through the band. It reached the room and came back lighter, like something tested and set aside.

The tunes grew slower. The bass went deeper. Leon’s horn stopped flirting and settled into something straight. Lottie stripped the chords down to what they needed.

The room listened more than it moved.

Somewhere behind the bar, in a lull, the radio crept back on—too loud for a second.

“…Department regrets…”

“…sunk in action…”

Gus snapped it down fast. No one commented. No one wanted to hear the rest.

Midway through the set, in a pause, a man drifted up too close to the stage.

He wore a good coat. Not dock wool. Not Navy issue. Something finer. His hat sat on his head like he wasn’t used to taking it off indoors.

“You’re Ivory,” he said, like it was something he owned or hoped to.

“That’s what they call me,” Ivory said. Beside him, Calvin lay on a heartbeat, a steady pulse.

The man smiled. “Best drummer and singer this side of the river, they say.”

Ivory shrugged. “Depends on who you ask.”

The man leaned in. “I’m in the record business… I’d like to talk to you after your set.”

The room tightened. Ivory felt it in the way Calvin’s bass line stiffened, the way Leon’s jaw set. Lottie’s hands stayed on the keys, but she didn’t play.

Ivory kept his face neutral, shook his head. “Now’s not the time.”

The man frowned. He wanted agreement. He wanted the comfort of it.

“Why not?” the man asked. “We’d want you in a studio for a check, but you got something boy… a sound.”

Ivory met his eyes. Held them. He’d been known as ‘The Drummer Boy’ since he was eight years old, wandering the streets. But that ‘boy’ coming from this man was not in that tone.

“You got a request?” Ivory said.

The man blinked, then laughed as if that was the right answer. “Play something Christmas but different,” he said. “Make it sound nice.”

He wandered off.

The band came back in. The tempo dropped. The sound thickened. Whatever lightness had been there drained away.

This was still music. It just wasn’t pretending anymore.

Ivory kept playing. He watched Gus from the corner of his eye. Watched the man in the fine coat who studied him. Watched the woman at the edge table, still not looking up.

The second set narrowed. The bass walked slower. The piano left space instead of filling it. Leon played fewer notes and made them count.

The room leaned forward without knowing why.

Ivory felt the paper in his pocket again, heavier now that the night was moving. He didn’t touch it. He didn’t need to.

He finished the set and let the sticks and brushes rest on the snare.

Applause came, steady but restrained, like people weren’t sure how much was appropriate anymore.

Ivory stood and stepped from the stage.

The hallway behind the bar smelled like mop water and old paper. The radio silent now.

Ivory leaned back against the wall and closed his eyes.

If he didn’t play the song now, it would follow him out the door. It would sit in his chest through training, through nights he wouldn’t sleep, through mornings that would come too early. It would turn bitter.

He reached into his pocket and felt the folded paper. He didn’t open it.

He didn’t need to.

He straightened and squared his shoulders.

The decision had already been made for him.

The timing hadn’t.

Ivory came back to the stage without announcement.

Calvin looked up first, reading his face. Leon’s eyes narrowed a fraction. Miss Lottie didn’t look at all. She waited.

Ivory sat and lifted his sticks.

The room didn’t hush all at once. It never did. But the noise thinned. Chairs stopped shifting. Glasses settled. A laugh near the bar died halfway out of someone’s mouth.

Lottie said, low, “You playin’ it.” She nodded to Leon, who relaxed, became a listener, not a player, then to Calvin, who lifted his bass.

Ivory leaned toward the microphone. The metal was cold. He felt it in his breath before his lips ever touched it.

He tapped the rim once. Not a count for them. Just enough to wake the drum.

Calvin’s bass found the floor slowly, carefully, like it didn’t want to stray. The piano stayed back, silent. Leon’s sax leaned against the wall, bell down, unneeded but waiting.

“They called me to the night, pa rum pum pum pum.”

The words came out low, placed instead of sung.

“The city’s dark delight, pa rum pum pum pum.”

The neon sign in the window buzzed faintly, its hum threading through the room. Somewhere beyond the walls, a ship’s horn sounded—long, mournful, moving away.

Ivory didn’t look at the room yet. He watched the drumhead, the way light broke across its worn surface. He’d sat here hundreds of nights. Tonight felt different because it was the last of the numbered.

“I brought no gifts, no gold, just my drum—”

He didn’t need to emphasize it. The truth of it was already there. Sticks. Wood. A beat he’d carried longer than anything.

The bass leaned closer. The room listened.

When Ivory lifted his eyes for the chorus, the room was already quiet.

“Oh, play for the shadows, play for the smoke—”

The word shadows stretched just enough to catch the corners, the back booth nobody used, the cracked mirror behind the bar, the door that never quite shut.

“For dreams that unravel, for words left unspoke.”

A woman near the bar stopped stirring her drink. The spoon clinked once and went still. A dockman folded his hands together, then let them rest on his knees.

“The boy with no riches, just rhythm and tone—”

Ivory let the snare speak here. Firm. Straight. Not pretty. The kind of beat you could walk to, or march to, or follow from a room without turning back.

“He plays for the broken, the lost, the alone.”

Nobody clapped. Nobody spoke. The line settled and stayed.

Ivory dropped his gaze again. The beat thrummed. The bass rolled darker now, heavier. Chords like resignation without drama.

“I see her there, her eyes ask why—”

He didn’t finish the line aloud.

She was exactly where he knew she’d be, near the edge of the light. Her coat was off now, draped over the back of the chair like she was ready to leave quickly if she had to. Her hands folded in her lap. She looked at him without asking anything.

Her smile, when it came, was small. Not encouragement. Not forgiveness. Recognition.

Ivory let the drums carry the rest of the verse. The rhythm softened, then tightened. He didn’t trust his voice with it.

“I played for the sinners, the saints all asleep—”

The line landed without weight added. Not crying, not singing—just telling it straight. Smoke, breath… and echoes in the room.

“For secrets unspoken—”

The bass dropped lower. Ivory’s hands moved without looking now. Sticks and brushes. Rim to head. The snare passed notes it didn’t want to sing aloud.

He thought of the folded paper in his pocket. Clean type. Official language. A future that didn’t care what he loved.

He eased back into the chorus but didn’t give it to them whole.

“For dreams that unravel,” he shot a look at the woman, “for words left unspoke—”

That was enough.

The rest lived in the way the room leaned forward, the way no one looked away.

Ivory slowed the tempo. Thickened the beat. Each strike landed with care, like he was setting something down so it wouldn’t break when he left it behind.

The final line came quiet, almost spoken.

“The little drummer boy, his song is done.”

He let the note hang.

Then he cut it clean.

For a moment, nothing moved. Then the applause came—not loud, not wild, but steady, like people were afraid to stop too soon.

Ivory nodded once and sat back from the kit.

The rhythm stayed in his hands as he stood. Followed him from the stage. Followed him down the narrow hall toward the door.

Outside, the cold waited.

Ivory didn’t go far at first.

He stood just outside the club door, under the shallow awning that did a poor job of keeping snow off his shoulders. The harbor air bit into his lungs. His breath came out in white, fast puffs. Inside, the noise returned cautiously—chairs shifting, voices testing themselves, a laugh that rose too loud and then backed down.

He could have walked away. He could have kept moving until the city hid him, the war swallowed the world, and nobody expected anything else from him.

But he hadn’t packed his sticks. He hadn’t said anything to Calvin, Leon, or Lottie. And he hadn’t spoken with her yet.

He went back in.

The room had changed. After a song like that, it always did. People didn’t look at him like entertainment anymore. They looked at him like a man who’d said something without asking permission.

Gus met him behind the bar. His face said, ‘You did it.’ It also said, ‘You hurt her.’ Necessary hurt, maybe, but hurt all the same.

“Drink?” Gus asked.

Ivory shook his head. His throat too full of smoke and words he’d yet to say.

Calvin came over first. He didn’t clap Ivory on the back. Didn’t make a joke.

“That was straight,” Calvin said.

Ivory nodded. That was enough.

Leon stood near the stage with his sax case open, fingers resting on the horn like it might bolt. “You made it sound like it was about us,” he said.

“It is,” Ivory said.

Leon shook his head once. “Don’t go making me sentimental.”

Miss Lottie approached last. Her hands were in her coat pockets. She looked at Ivory the way she looked at anything she meant to be honest about.

“That chorus,” she said. “You make people listen like that; you’re trouble.”

Ivory almost smiled.

She studied him for another second. “Take care of your hands,” she said. “This place won’t get better without music.”

Then she nodded once and walked away, having said all she intended to.

Ivory sat on the edge of the stage and began breaking down the kit. He loosened the snare. Wiped the cymbal with a cloth. Put the brushes away carefully.

He was halfway through when a shadow fell across the floorboards.

He looked up.

The woman stood there, her coat back on, hat pulled low. Up close, her eyes looked tired—not from lack of sleep, but from carrying herself through a year that didn’t leave people much room to rest.

Ivory stood. Some habits were older than pride.

“You didn’t have to come,” he said.

“I know,” she said.

They stood there a moment, the club noise moving around them like water around stone.

“You got the notice,” she said.

It wasn’t a question.

Ivory nodded. “Yeah.”

“How soon?”

“After Christmas,” he said. “Few days.”

She took that in. “I won’t write foolish letters,” she said. “I won’t ask you for promises.”

Ivory swallowed.

“But if you come back,” she said, “you find me.”

His chest tightened hard enough to hurt.

“And if I don’t?” he asked before he could stop himself.

Her face didn’t change. “Then I’ll remember you as a man who played honestly when it mattered.”

She lifted her hand and touched his sleeve—two fingers only, light and deliberate.

Then she stepped back.

“That’s enough,” she said.

It was.

She turned and walked toward the door. At the threshold, she paused just long enough to look back once. Not longing. Not tragedy. Recognition.

Then she was gone, swallowed by cold and harbor air.

Ivory stood alone for a moment longer. The room reclaimed itself. Glasses clinked. Someone laughed, trying to shake the feeling off.

Gus called, “You need help with that?”

Ivory shook his head.

Calvin came over anyway and lifted the bass drum case without asking.

“You sure?” Calvin said.

Ivory watched the door. “I’m sure,” he said, meaning: I’m sure about nothing.

Leon slung his horn case over his shoulder. “See you after,” he said.

They didn’t say if. They didn’t say when.

Miss Lottie buttoned her coat near the door. “Keep the beat,” she said to Ivory. “However you can… you have to.”

He nodded.

When the room finally thinned, Ivory took his coat from the chair and put it on. He slipped his sticks into the inside pocket—where they belonged. With him. Like a talisman. Like proof.

Before he left, he looked once more at the sagging garland and the tired evergreen shedding needles into its bucket.

Christmas wasn’t ruined. It was strained. Stretched thin over a world that didn’t have much patience for prettiness anymore.

Outside, the dock wind slapped him.

The harbor smelled like salt, oil, and cold iron. A ship’s horn sounded again, farther off this time, sliding into the distance.

Ivory walked along the edge of the wharf. The planks creaked under his shoes. Water moved black below, swallowing light.

Behind him, the club door closed with a soft, final sound.

He kept walking.

And the rhythm he’d set inside—the hush, the pulse, the steady insistence of what still mattered—followed him into the night, dissolving into the sound of his footsteps on the dock as if the city were trying, and failing, to keep time.